Crypto Intelligence Report on the November 27, 2025 Upbit Security Breach

December 02, 2025

Disclaimer

This report has been prepared based on publicly available on-chain transaction and address data. Due to limitations in the timing of data collection and verification, as well as the data sources used, certain figures and estimates may contain a margin of error. The analysis and assessments in this report may also be subject to change if additional on-chain data, exchange disclosures, or investigative findings become available in the future.

1. Executive Summary

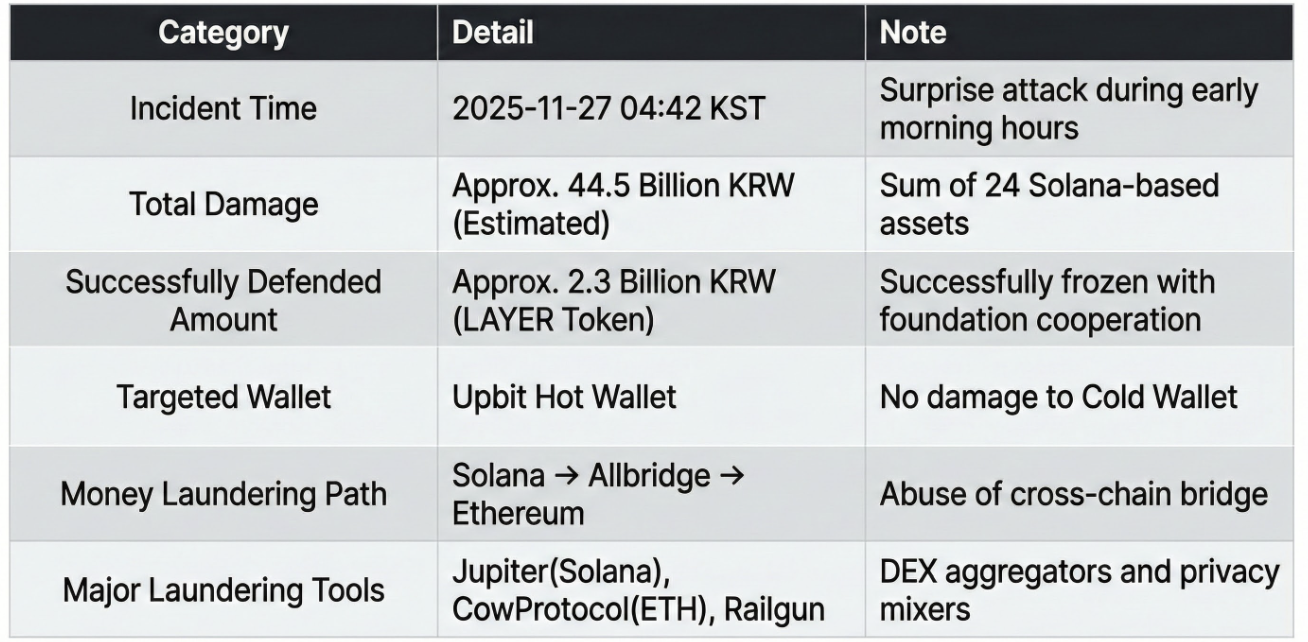

1.1 Incident Overview and Key Intelligence

At 04:42 KST on November 27, 2025, abnormal withdrawal transactions were detected in the Solana-based Hot Wallet infrastructure of Upbit, Korea's largest virtual asset exchange. Cross-analysis of on-chain forensics and public information suggests the incident occurred due to an external attacker gaining unauthorized access to the hot wallet's signing key or the infrastructure responsible for signing authority.

Cold Wallets and separately stored assets were not directly affected by this incident, and the damage was limited to assets held in the hot wallet infrastructure, which was online.

The total estimated damage is approximately 44.5 billion Korean Won, consisting of 24 SPL tokens based on the Solana network. Among these, approximately 2.3 billion Korean Won worth of 'LAYER' tokens were frozen with the prompt cooperation of the issuing foundation and excluded from the final loss amount.

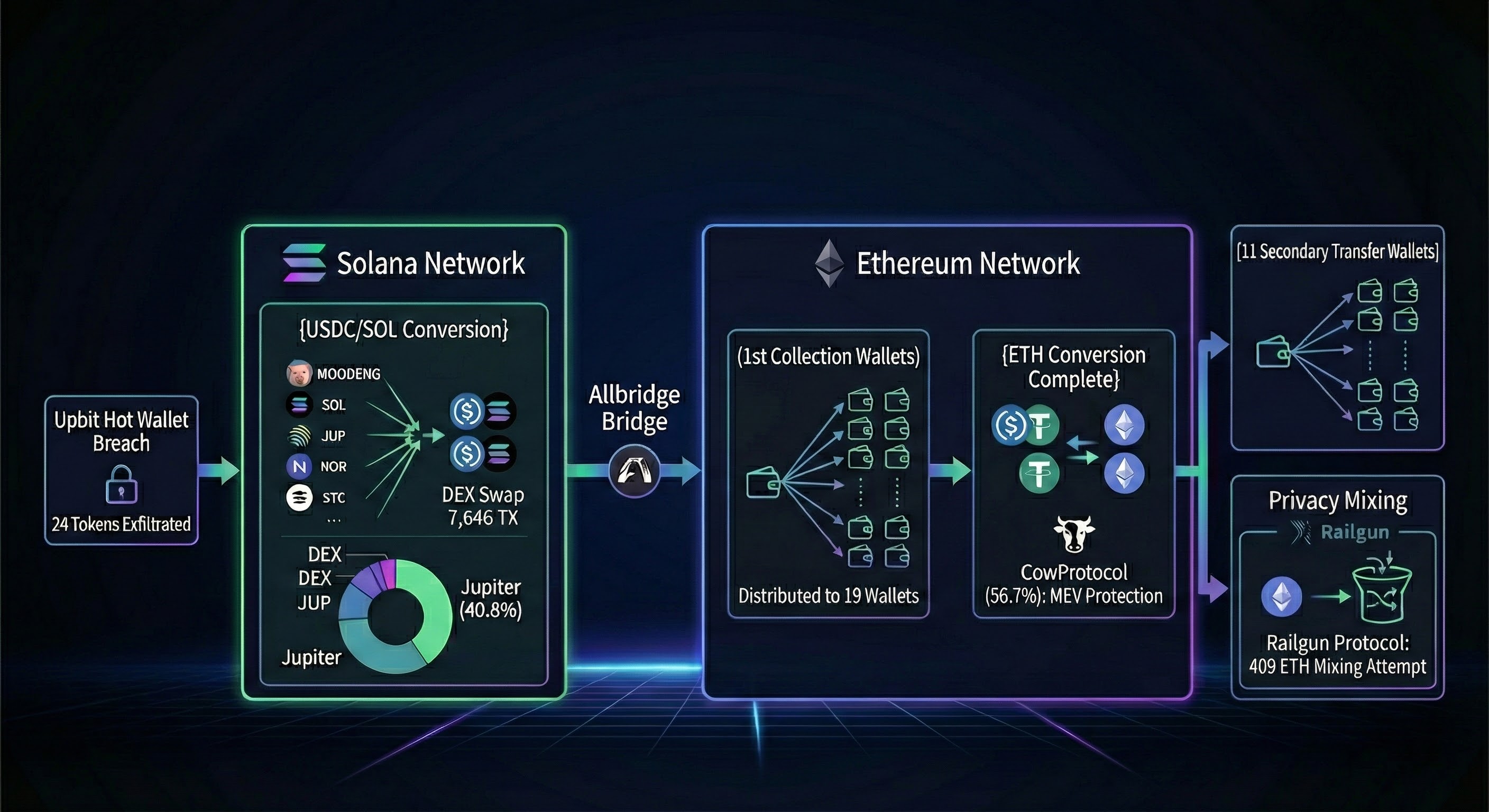

To liquidate the stolen assets and reduce the risk of tracing and freezing, the attacker used a sophisticated laundering tactic combining Chain-Hopping and privacy protocols. The overall flow can be summarized in the following four stages:

- Theft and initial swap on Solana

- Asset restructuring focused on USDC via Solana DEXs

- Entry into Ethereum via Allbridge (Cross-Chain Bridging)

- Distribution and conversion on Ethereum, followed by the use of privacy protocols like Railgun

1.2 Key Metrics Summary

The main quantitative metrics related to the incident were compiled by cross-verifying Upbit's public disclosures and on-chain data.

1.3 Summary of Fund Flow and Laundering Stages

To complicate tracing, the attacker opted for a multi-stage process of fragmenting the stolen funds and combining different infrastructures. The main stages we identified are as follows:

- Exfiltration: Theft of 24 diverse altcoins.

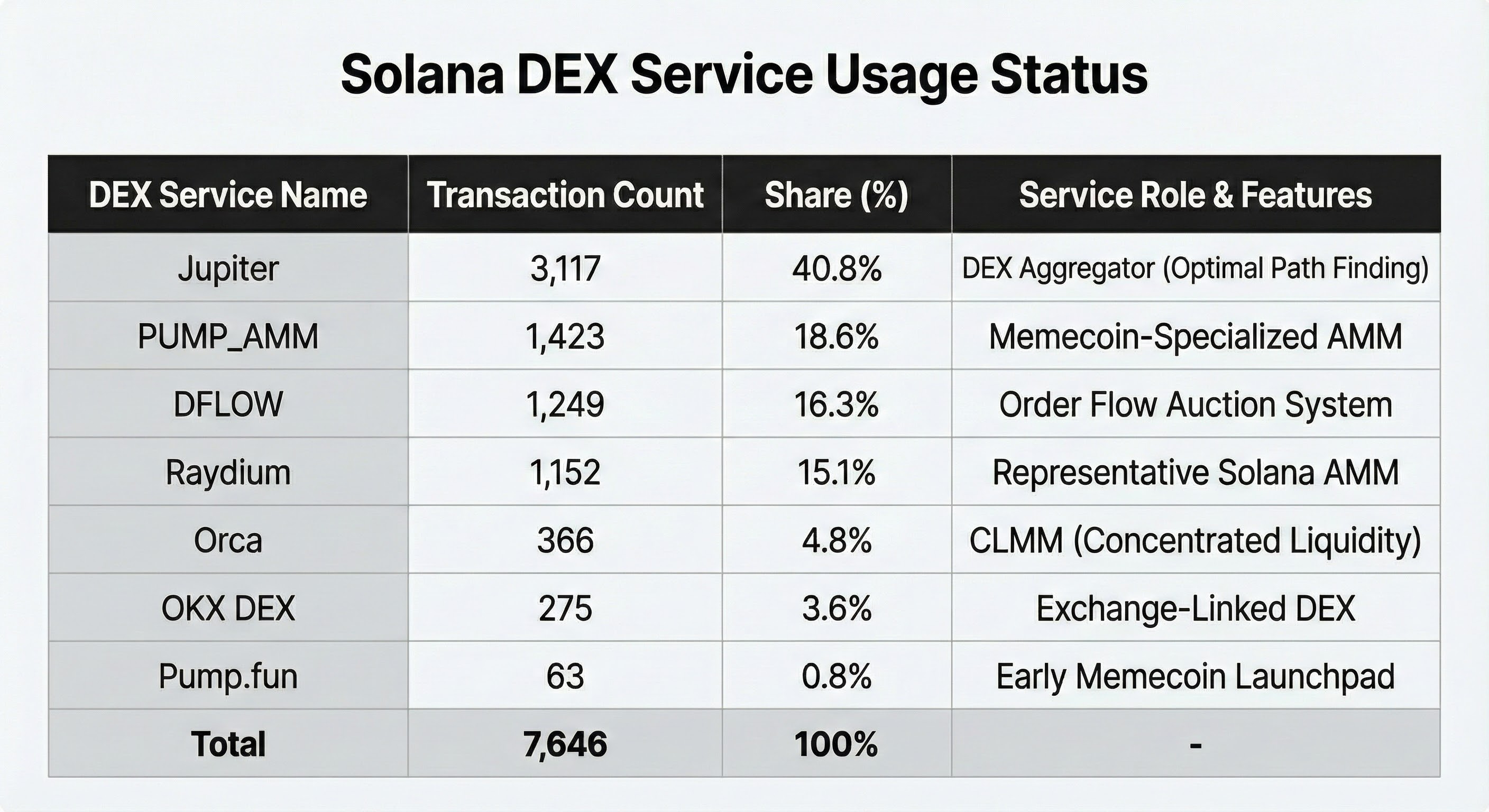

- Solana DEX Swap: Rapid conversion of illiquid altcoins to USDC, the preferred stablecoin, via aggregators like Jupiter (40.8%). A total of 7,646 transactions occurred.

- Cross-Chain Bridging: Transfer of approximately $22.12 million (approx. 32.5 billion KRW) to the Ethereum network using Allbridge.

- Layering (Fund Distribution): Funds were split and received across 19 primary recipient wallets on Ethereum.

- ETH Conversion: Conversion of easily traceable and potentially frozable USDC/USDT into censorship-resistant ETH. CowProtocol (56.7%) was mainly used during this process to defend against MEV (Miner Extractable Value) attacks.

- Obfuscation: Attempted mixing of 409 ETH using the Railgun privacy protocol to break the chain of custody.

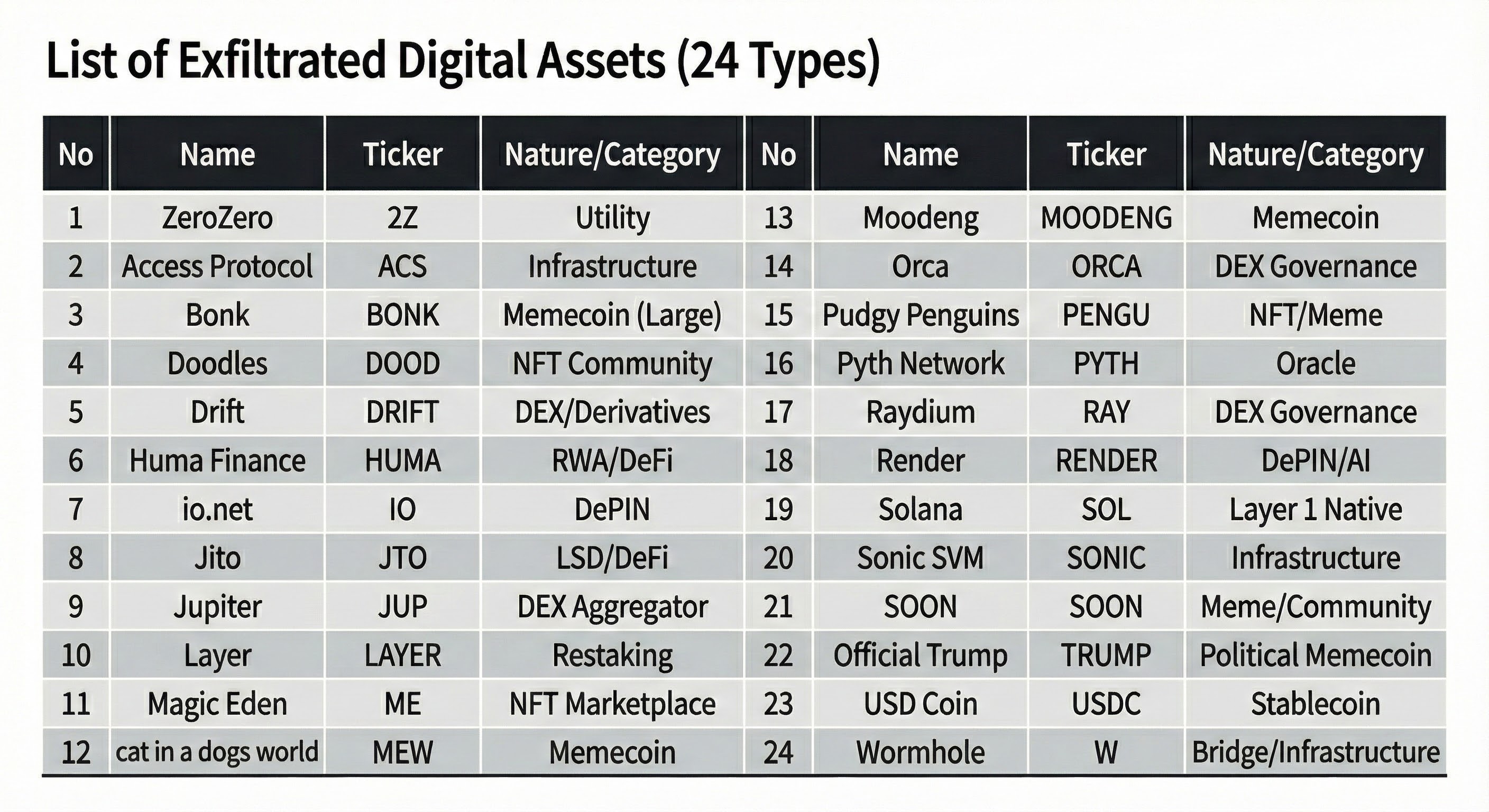

2. Detailed Analysis of Stolen Assets

One feature of this incident is that the attacker did not target only specific major assets (BTC, ETH, etc.) but rather swept 24 different Solana-based tokens with varying liquidity and market capitalization. This indicates that the attacker did not apply a specific filter to asset selection but moved to recover as many accessible assets as possible from the hot wallet.

2.1 List of Stolen Digital Assets (24 Types)

The data below lists all the stolen assets. The attacker would have needed to devise a sale strategy tailored to the liquidity situation of each token to liquidate this diverse set of assets.

From an intelligence perspective, the following points are noteworthy:

- Assets with High Liquidity Constraints: Small meme coins and project tokens such as MOODENG, 2Z, and SOON have shallow liquidity pools, causing significant slippage during large-volume sales. The attacker likely had to rely on DEX aggregators like Jupiter, which feature path-finding capabilities, to quickly dispose of these assets.

- Inclusion of Stablecoins: USDC was already included in the list of stolen assets, meaning it could have been bridged immediately without a separate swap. Nevertheless, the attacker chose to mix it with other tokens during transfer to dilute the pattern. This suggests prioritizing increasing the tracer's analysis time over simplicity.

3. Phase 1: Fund Laundering and Swap Analysis within the Solana Network

The attacker's initial goal on Solana was to consolidate the too-diverse collection of tokens into highly liquid and compatible assets (USDC, WSOL, etc.). This can be seen as a preparatory phase for bridging to Ethereum.

3.1 Solana DEX Service Usage Status (Based on Unique TXs)

The attacker did not rely on a single DEX but used multiple services concurrently, generating a total of 7,646 swap transactions.

Analysis – Reason for Using Jupiter

Jupiter is an aggregator that pools liquidity from major DEXs within Solana and splits orders across multiple paths. It is optimized to reduce price impact during large-volume sales. From the attacker's perspective:

- They needed to consolidate various tokens at the highest possible realized value.

- Price distortion increases the risk of tracing and detection.

An aggregator like Jupiter, which splits orders and utilizes multiple pools simultaneously, was a virtually essential choice. The 18.6% usage share of PUMP_AMM also supports the fact that a significant number of stolen assets were PUMP-related meme coins.

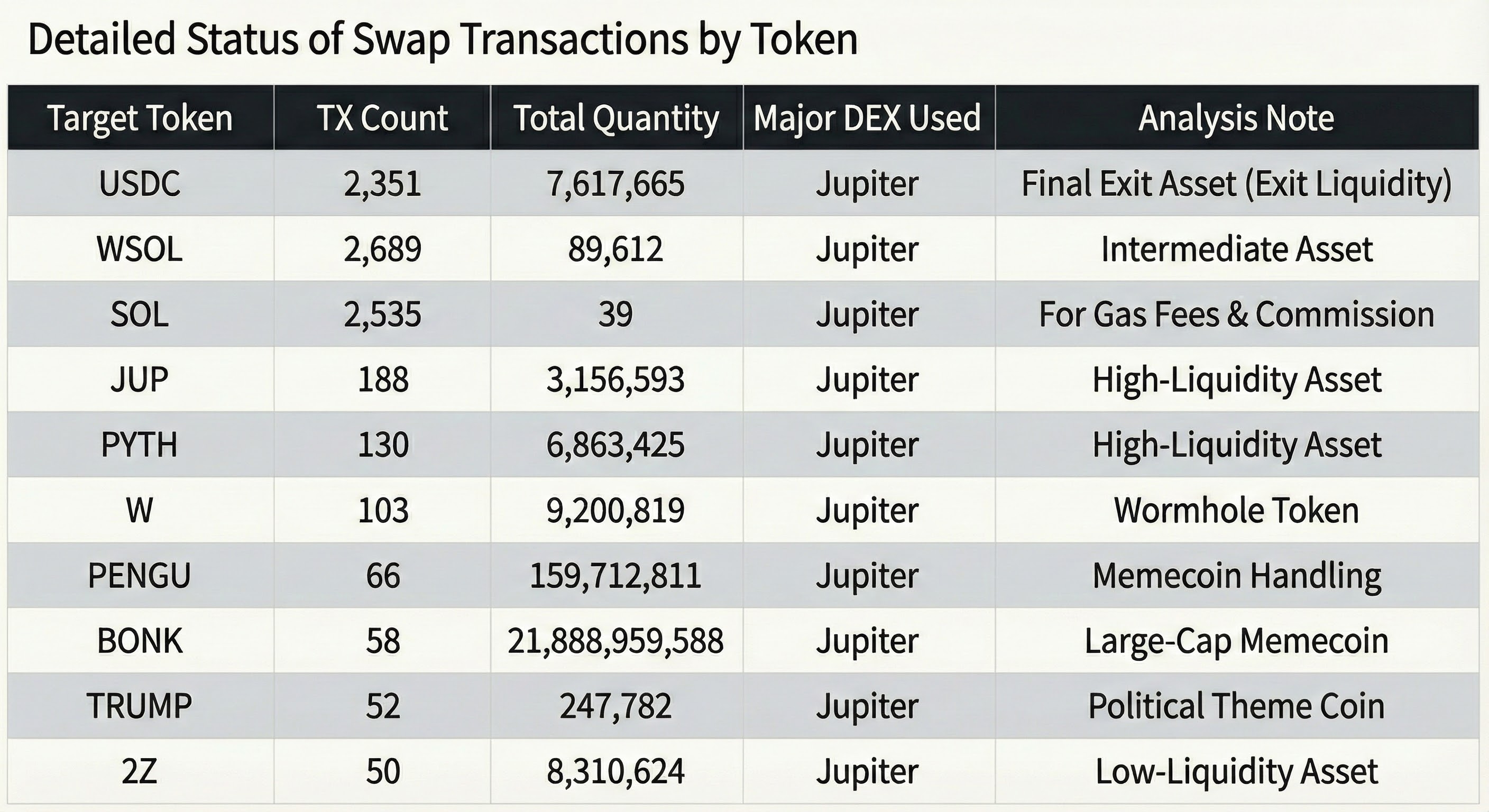

3.2 Detailed Status of Swap Transactions by Token

The transaction patterns for each asset give an insight into which tokens were "difficult to process."

The excessive number of WSOL-related transactions (2,689) indicates that many tokens did not go directly to USDC but followed a multi-stage path such as Token → WSOL → USDC. This process itself complicates the transaction graph, increasing the time required for forensic analysis as a side effect.

4. Phase 2: Cross-Chain Fund Transfer Using Allbridge

The funds, which were somewhat "consolidated" on Solana, were moved to Ethereum via Allbridge. This is interpreted as an attempt to:

- Avoid the risk of freezing/sanctions within the Solana ecosystem.

- Utilize Ethereum's infrastructure, which still hosts various privacy tools even after Tornado Cash.

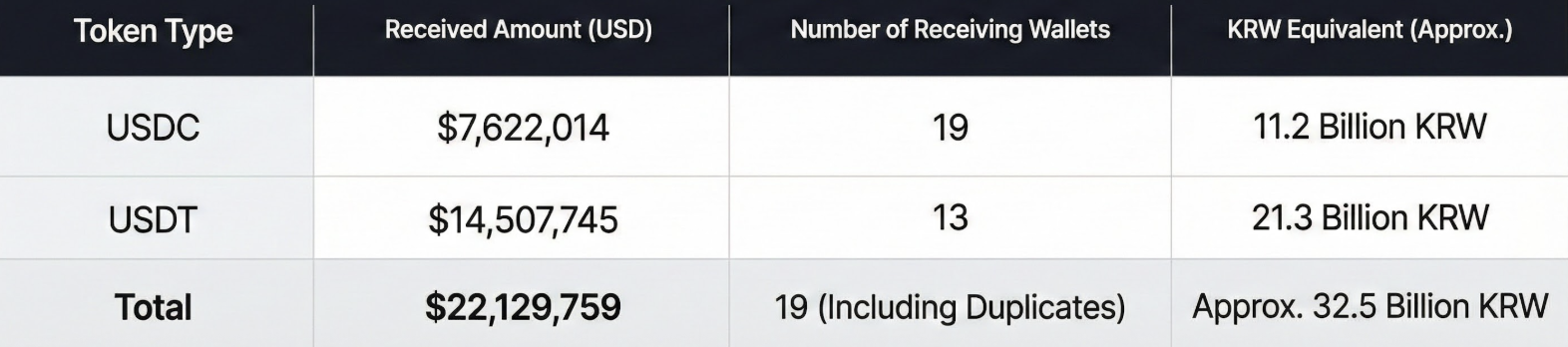

4.1 Allbridge Received Fund Volume

The funds that flowed into Ethereum via Allbridge are summarized as follows:

The funds that flowed into Ethereum via Allbridge are summarized as follows:

- USDC: Approx. $7,622,014, received by 19 wallets (including duplicates)

- USDT: Approx. $14,507,745, received by 13 wallets

- Total: Approx. $22,129,759 (Approx. 32.5 Billion KRW, subject to exchange rate fluctuations)

Although the proportion of USDC had already been increased on Solana, some was converted to USDT during the transfer to Ethereum. It is necessary to consider both the possibility that this happened automatically due to Allbridge's liquidity pool structure and the possibility that the attacker sought to distribute risk by fragmenting stablecoins.

4.2 Bridge Timeline Analysis (Operational Timeline)

- Bridge Start: 2025-11-27 19:10:53 KST (Approx. 14 hours and 30 minutes after the incident)

- Bridge End: 2025-11-28 05:48:29 KST

- Total Duration: 10 hours 38 minutes

A notable observation here is that the funds were not moved "all at once in a hurry."

- Liquidity Management: Bridge pools have limited liquidity on both chains. Pushing too large an amount at once can result in failure, delay, or unfavorable exchange rates. The attacker avoided this by dividing the amount and transferring it over time.

- Monitoring Evasion: The fragmented transfer over 10 hours also has the effect of relatively lowering the attention of monitoring systems targeting large fund movements, such as 'Whale Alert'. This can be seen as applying the 'Smurfing' technique to the bridge timing.

5. Phase 3: Ethereum Aggregation Wallets and Distribution Analysis (Tracking & Tracing)

The funds transferred to Ethereum were first divided and flowed into 19 primary wallets, and then moved again to 11 secondary wallets. Subsequently, a portion was incorporated into Railgun, breaking the chain of custody.

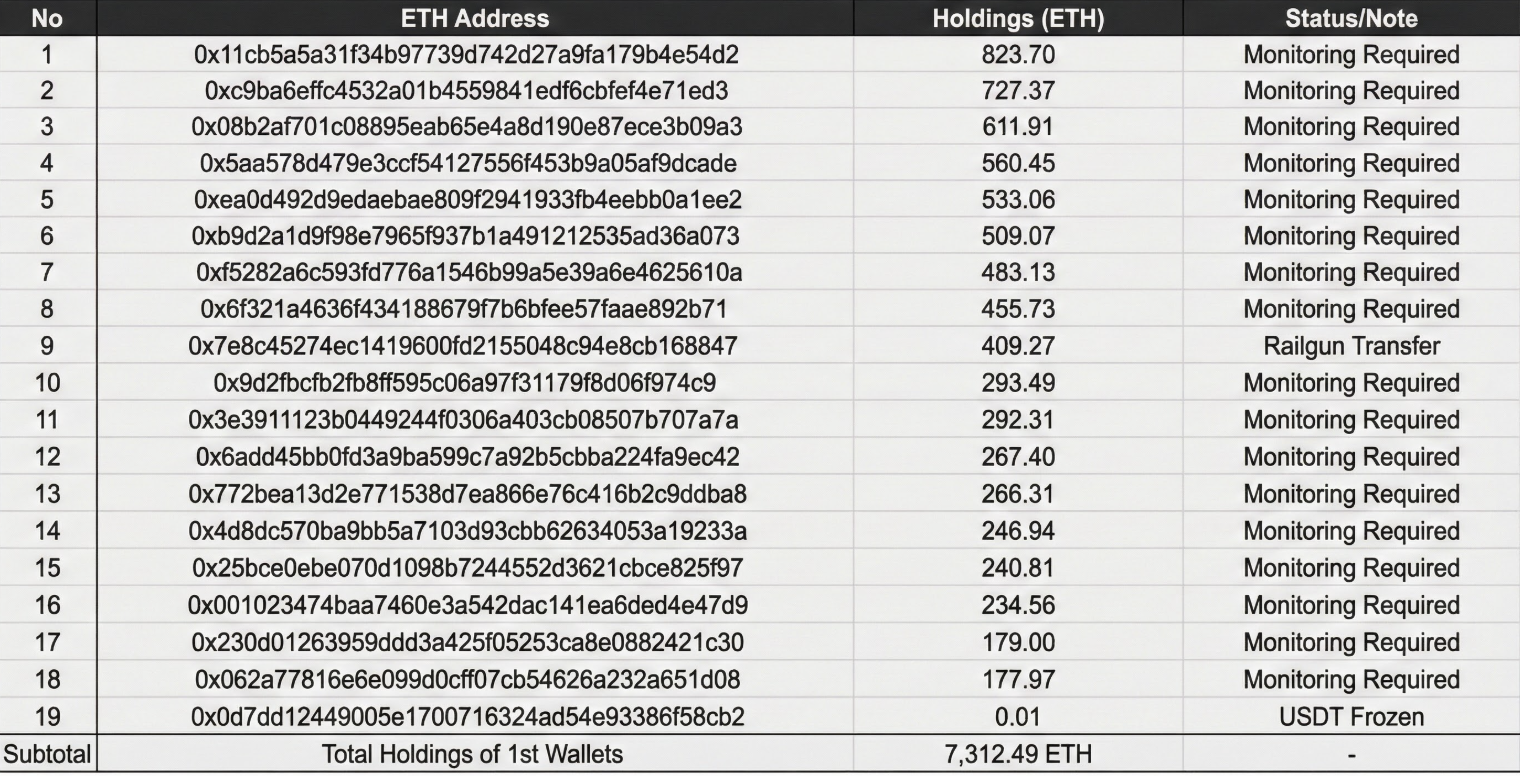

5.1 List of Primary Bridge Receiving Wallets (19)

These 19 wallets are the primary entry points that received funds directly from Allbridge. The ETH held by each wallet is as follows:

Regarding the actions taken, approximately $10,159 (approx. 14 million KRW) in USDT held in wallet #19 was frozen by Tether. This shows that some addresses were blacklisted, but the majority of the remaining assets have already been converted to ETH, making the likelihood of freezing very low.

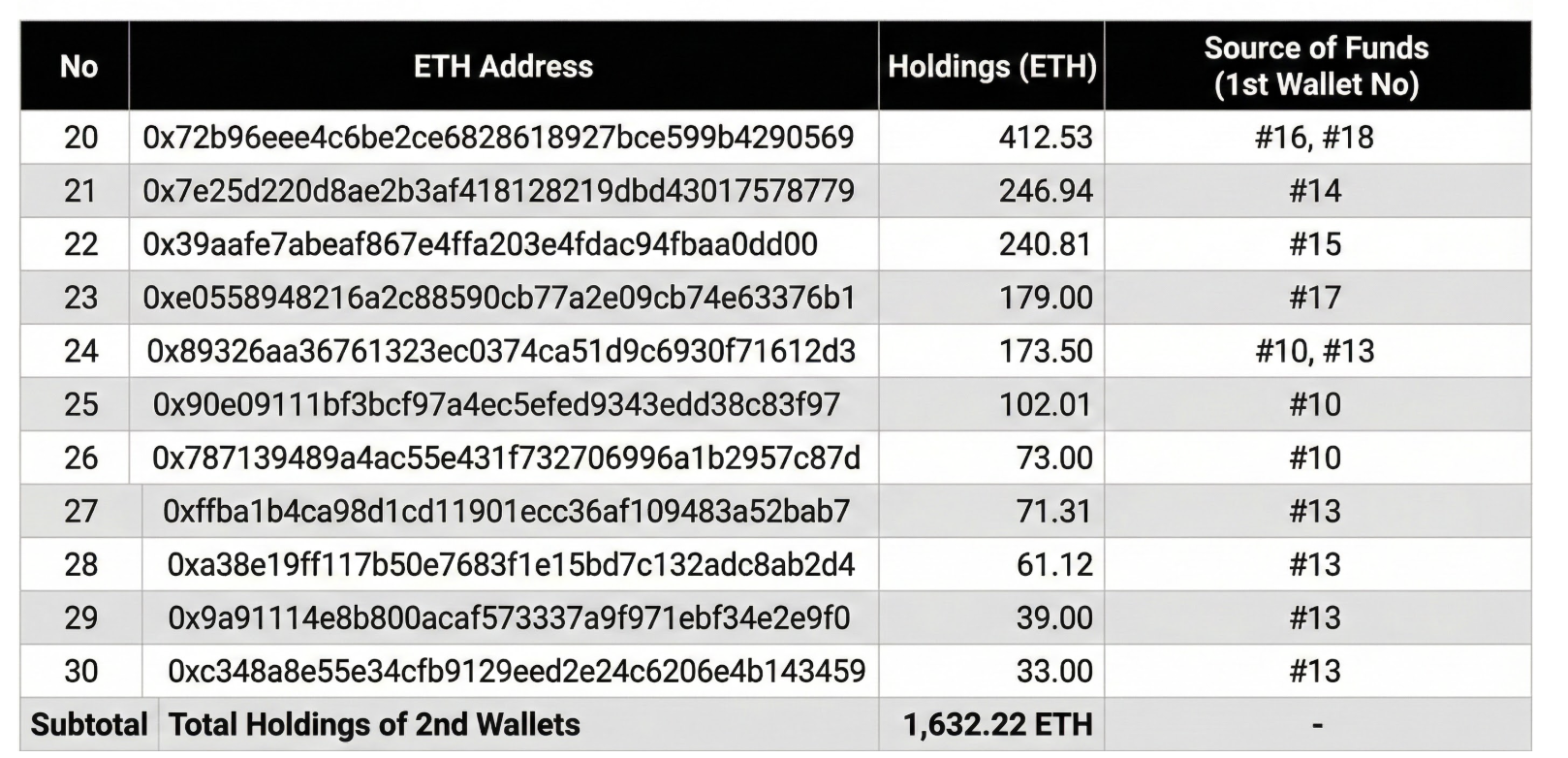

5.2 List of Secondary Movement Wallets (11)

A portion of the funds from the primary wallets was transferred to 11 secondary wallets. This is interpreted as a deliberate move to complicate the on-chain transaction graph and avoid simple patterns like "single wallet - single exit."

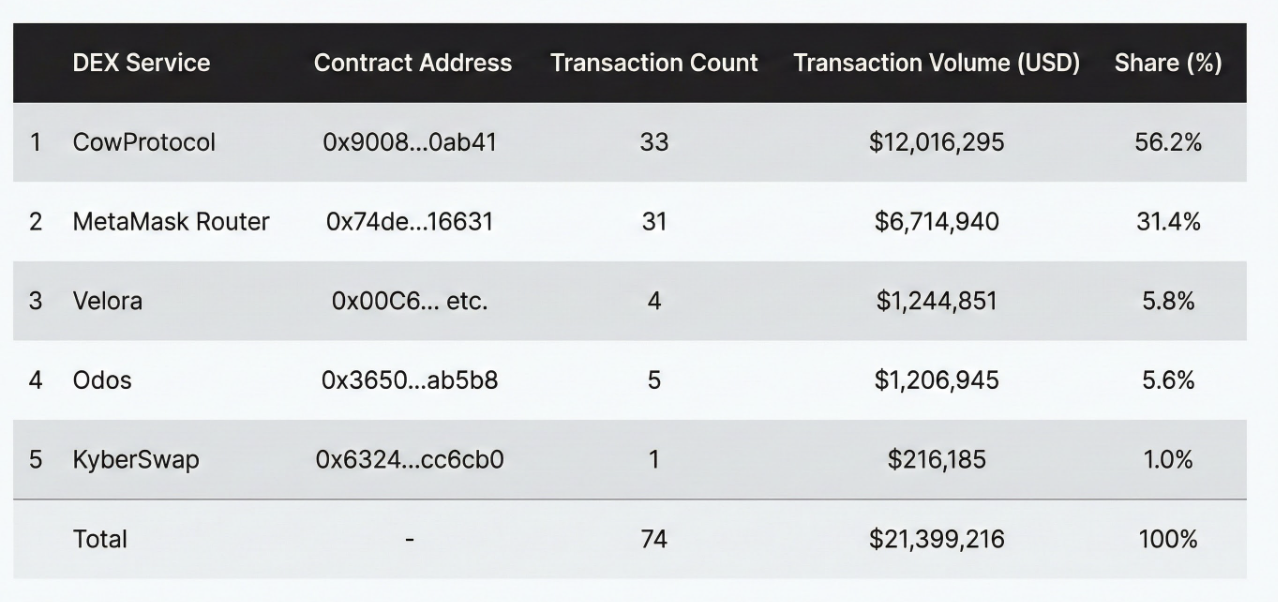

6. Asset Conversion Tactics on Ethereum: Utilizing CowProtocol

After entering Ethereum, the attacker's primary goal was to convert stablecoins (USDC, USDT), which have a high risk of freezing and are relatively easy to trace, into the native asset, ETH. The utilization rate of CowProtocol in this process was particularly noteworthy.

6.1 Ethereum DEX Service Swap Share

6.2 Rationale for Choosing CowProtocol

The fact that CowProtocol accounted for more than half of the total swap amount is highly significant. It demonstrates that the attacker had a considerable understanding of the MEV (Miner/Maximal Extractable Value) environment and sandwich attack structures on Ethereum.

- When executing swaps of billions to tens of billions of KRW on conventional DEXs (like Uniswap), "Searchers" detect the transaction in advance and attempt a sandwich attack by placing orders before and after it. In this scenario, the attacker would exchange assets at a much worse price than intended.

- CowProtocol mitigates MEV risk by aggregating orders off-chain, processing them as a batch auction, and directly matching orders (Coincidence of Wants) when possible.

In summary, the attacker strategically chose CowProtocol over conventional DEXs to:

- Minimize slippage even with large-scale swaps.

- Avoid becoming a target for MEV bots.

- Conceal their transaction intent as much as possible.

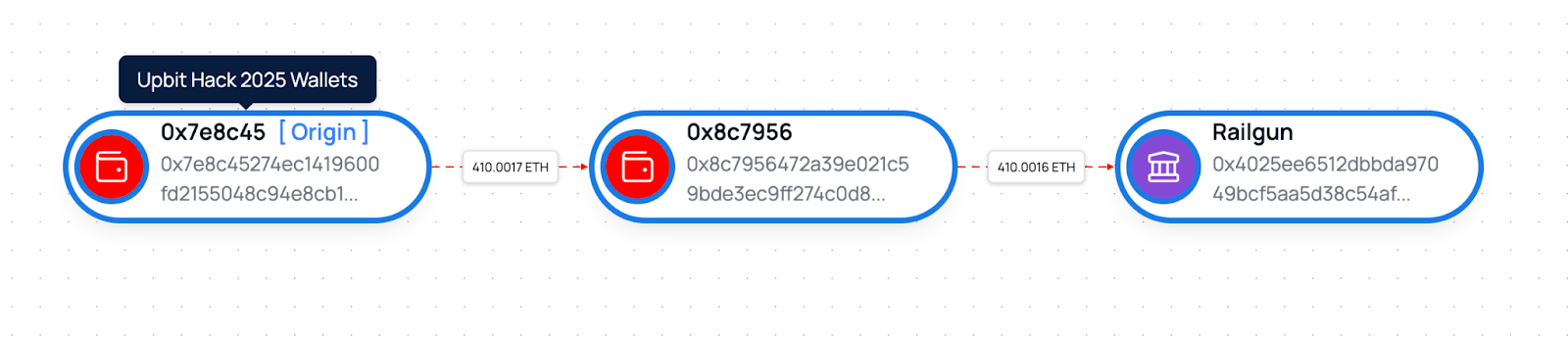

7. Privacy Obfuscation Phase: Utilizing Railgun

According to current understanding, a significant portion of the stolen funds remains traceable on-chain. However, approximately 409 ETH (roughly $1.2 million) flowed into the Railgun privacy protocol, making the subsequent flow virtually impossible to track through conventional means.

7.1 Railgun Movement Path Details

Source: CATV

- Source Wallet: 0x7e8c45274ec1419600fd2155048c94e8cb168847 (Wallet #9)

- Intermediate Transit: 0x8c7956472a39e021c59bde3ec9ff274c0d873c63

- Final Destination: 0x4025ee6512dbbda97049bcf5aa5d38c54af6be8a (Railgun Contract Interaction)

- Amount Moved: 409.27 ETH

7.2 Railgun Threat Level and Tracing Limitations

Unlike Tornado Cash, Railgun is a protocol built on zk-SNARKs, supporting private swaps internally beyond simple deposit/withdrawal mixing. When a user deposits funds, they are managed as a "Shielded Balance," and it is practically impossible for external parties to determine who sent how much to whom.

Unless the attacker shares their Viewing Key, recovering the subsequent flow through on-chain forensics alone is extremely difficult. Although techniques like PoI (Proof of Innocence) are being discussed, Railgun entry is realistically considered a "flow cutoff point."

A particularly noteworthy point is that the amount sent to Railgun is relatively small compared to the total estimated stolen volume:

- Total Estimated Stolen ETH: Over 7,300 ETH

- Railgun Inflow: Approx. 400 ETH

This suggests the attacker first conducted a "test transfer" to check:

- Protocol functionality

- Liquidity and technical risks

- Monitoring response

They may then sequentially inject the remaining funds as the situation evolves. In other words, the 409 ETH transfer to Railgun might be the beginning, not the end.

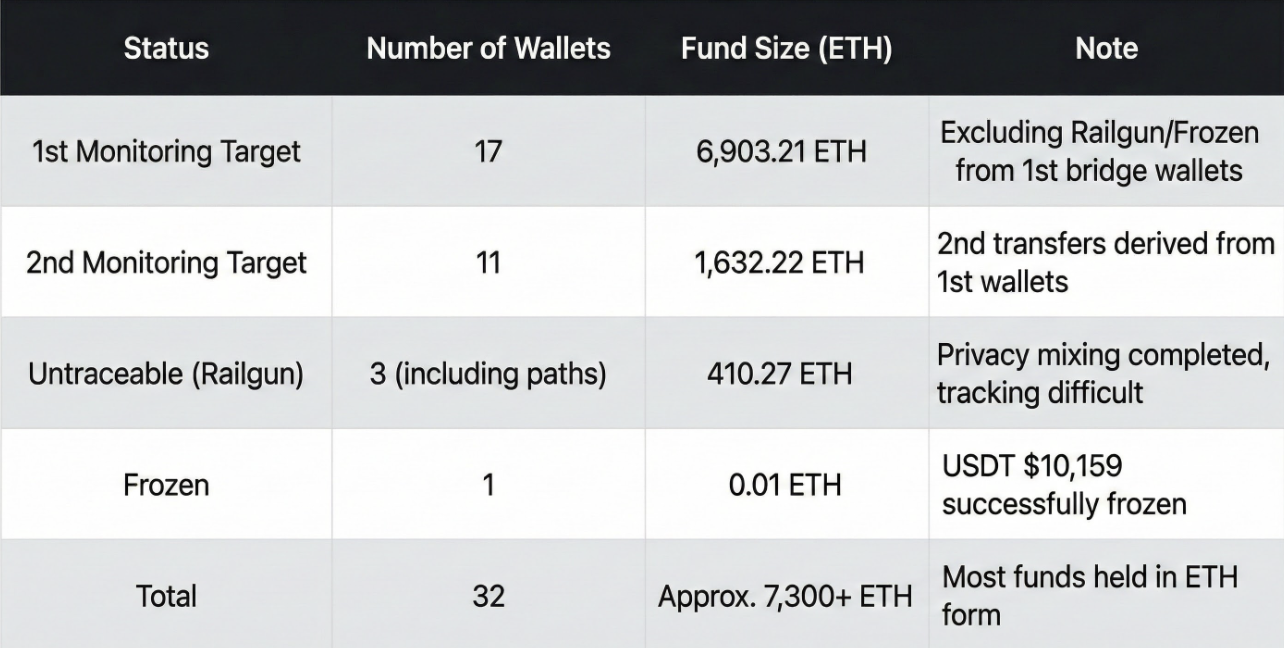

8. Final Fund Status Summary and Conclusion

8.1 Fund Status Classification Table

The current status of the funds is summarized as follows:

Primary Monitoring Target Wallets

- Target: 17 wallets

- Volume: Approx. 6,903.21 ETH

- Description: Remaining assets in primary bridge wallets, excluding Railgun transfers and frozen amounts.

Secondary Monitoring Target Wallets

- Target: 11 wallets

- Volume: Approx. 1,632.22 ETH

- Description: Amount of secondary movement derived from primary wallets.

Untraceable (Railgun Inflow)

- Target: 3 (Including path)

- Volume: Approx. 410.27 ETH

- Description: Incorporated into Railgun, making on-chain tracing virtually impossible.

Frozen

- Target: 1 wallet

- Volume: USDT $10,159 equivalent

- Description: Freezing action completed by Tether.

Total

- Total Wallets: 32

- Total Volume: Over 7,300 ETH (ETH standard, KRW conversion subject to price fluctuations)

Overall, a substantial amount of ETH remains concentrated in specific wallets, and it is realistic to consider the attacker in a "waiting phase," preparing for the next step as market and investigative attention wanes. The remaining approximately 6,900 ETH has a high likelihood of being moved further to Railgun or other privacy tools. It is a realistic approach to not view this incident as a concluded hack but as a medium-to-long-term tracing challenge that may continue for several months, and to structure monitoring and collaboration strategies accordingly.

8.2 Conclusion and Security Recommendations (Actionable Intelligence)

This incident is not a simple key leakage but a case of sophisticated virtual asset crime that comprehensively exploited the DeFi infrastructure of both the Solana and Ethereum chains. The step-by-step use of Jupiter, Allbridge, CowProtocol, and Railgun gives the impression that the attacker fully understood the on-chain structure and regulatory/freezing mechanisms.

The immediate necessary response from a practical perspective is as follows:

1. Blacklist Sharing and CEX Collaboration

- All 32 Ethereum wallet addresses compiled in this report must be promptly shared with major global exchanges (Binance, Coinbase, OKX, etc.) and investigative agencies.

- Internal rules and response processes should be pre-established to enable automatic freezing and KYC information acquisition if an inflow from these addresses to a CEX is detected.

2. Continuous Monitoring of Railgun Withdrawal Patterns

- A 24-hour monitoring system must be maintained for 'Unshield' (withdrawal) transactions of approximately 400 ETH from the Railgun contract.

- Patterning the withdrawal time's gas price, transaction timing, and the destination wallet's past history can increase the probability of catching subsequent movements by the same attacker.

3. Cooperation with Solana, Bridge, and Exchange Parties, and Gas Fee Source Tracing

- It is necessary to backtrack the initial funding transactions (gas fee top-ups, etc.) of the attacker's wallets used on Solana to confirm which exchange or service supplied the funds.

- Specifically, this analysis confirmed traces of a small amount of ETH being transferred from Binance for gas fees to some Ethereum wallets (e.g., 0x7e8c45274ec1419600fd2155048c94e8cb168847 and associated addresses). Since the gas fee was sent directly to the Ethereum address from Binance, the exchange is highly likely to have KYC information, access IPs, and device information related to those addresses.

- Therefore, it is crucial to collaborate with Binance to conduct a reverse tracing operation from the "entity that sent the gas fee → associated exchange account → actual user." This is the key link to obtaining real-name and access information that is difficult to secure through simple on-chain analysis alone.

4. Re-evaluation of Hot Wallet Operation and Key Management Policies

- This incident again demonstrated how exponentially large the damage can become when signing authority is compromised in a hot wallet environment.

- It is necessary to re-evaluate and supplement overall hot wallet operating policies, including signing key management methods, access control to signing infrastructure, and transaction anomaly detection/blocking logic for large-scale withdrawals.

In conclusion, a significant amount of ETH remains in specific wallets, and the attacker appears to have entered a "waiting mode," anticipating a time when

the market and investigative attention loosens. The remaining approximately 6,900 ETH is very likely to be moved further to Railgun or other privacy tools.

The realistic approach is to regard this incident not as a concluded hack but as a medium-to-long-term tracing task that may continue for several months,

and to adopt monitoring and collaboration strategies accordingly.

106 reads