Trust Wallet Breach Report: Damage Assessment, Fund Flows, VASP Inflows, and Response Strategies

December 27, 2025

Disclaimer: This report is based on onchain data and publicly available information as of December 26, 2025. As investigations progress and additional data becomes available, new facts may emerge. Any determination of whether a specific wallet address is linked to criminal activity is ultimately up to the competent judicial and law-enforcement authorities. If you need an additional dataset or the underlying raw data, please contact at [email protected].

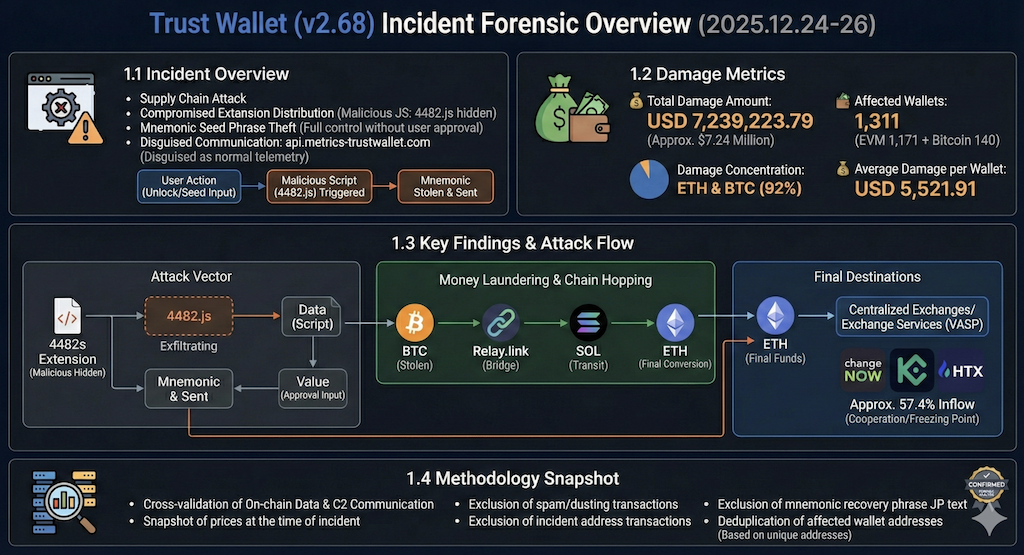

1. Executive Summary

1.1 Incident overview

This report presents a fact based forensic analysis of the Trust Wallet browser extension (v2.68) compromise observed between December 24 and 26, 2025. The evidence strongly suggests this was not a vulnerability in any blockchain protocol itself, but a supply chain compromise in the wallet extension’s distribution/update path.

The attacker injected a malicious JavaScript payload (4482.js) into the extension. The payload was designed to steal users’ mnemonic seed phrases at the exact moment the wallet is actively used (for example, unlocking the wallet or entering a seed phrase).

Once a seed phrase is exposed, the attacker can take full control of the wallet without any additional user approval. This is why losses can spread quickly and at scale in a short time.

1.2 Confirmed damage

Based on spot value at the time of the incident, the confirmed losses are:

- Total losses: USD 7,239,223.79 (about USD 7.24M)

- Victim wallets: 1,311 (EVM 1,171 + Bitcoin 140)

- Related transactions: 1,906

- Average loss per wallet: USD 5,521.91

Losses were observed across eight blockchain networks including Ethereum, Bitcoin, and Polygon. Roughly 92% of total losses are concentrated in Ethereum and Bitcoin.

1.3 Key findings

(1) Attack vector

Indicators suggest the malicious JavaScript (4482.js) embedded in extension v2.68 collected mnemonic seed phrases and transmitted them to api.metrics-

trustwallet.com. The traffic appears intentionally disguised as normal telemetry or error reporting, making it less likely to stand out in basic monitoring.

(2) Laundering via chain hopping

The attacker used a Relay.link-based cross-chain route to move value from BTC through SOL and into ETH. Repeated cross-chain moves sharply increase

tracing and recovery complexity and help evade single-chain monitoring and controls.

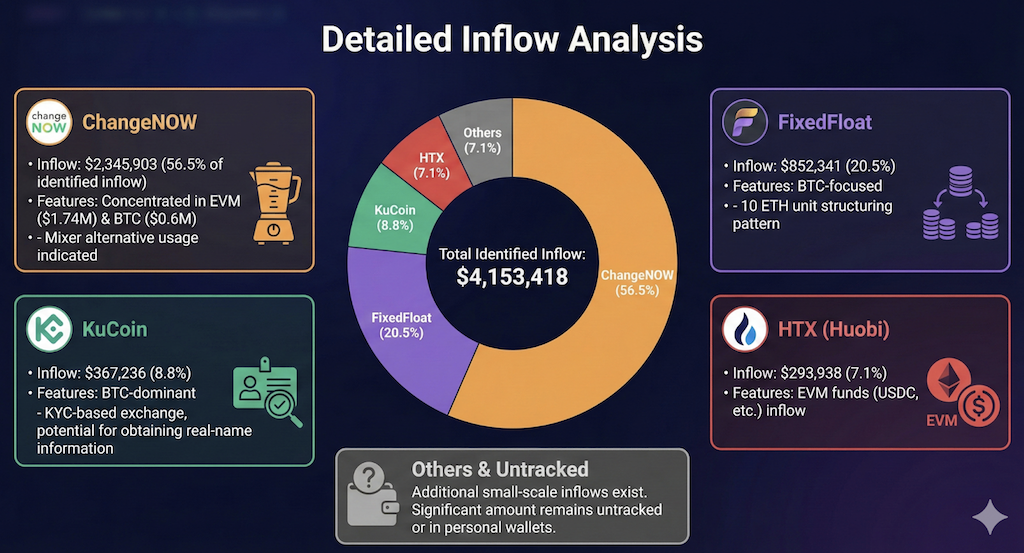

(3) Final destinations (service providers / VASPs)

Approximately 57.4% of the stolen funds (about USD 4.15M) are confirmed to have flowed into centralized exchanges and instant swap services. Major

identified destinations include ChangeNOW, KuCoin, and HTX. This layer is the most realistic point for freeze requests, investigative cooperation, and

recovery workflows.

1.4 Methodology snapshot

We derived conclusions by cross-validating on-chain transaction data against attacker infrastructure and suspected C2 communication patterns.

Loss valuation uses a price snapshot from the incident window. Illiquid tokens, spam like assets, and tiny dusting transfers were excluded. Victim counting is

based on unique wallet addresses with duplicates removed.

2. Incident Reconstruction and Technical Analysis

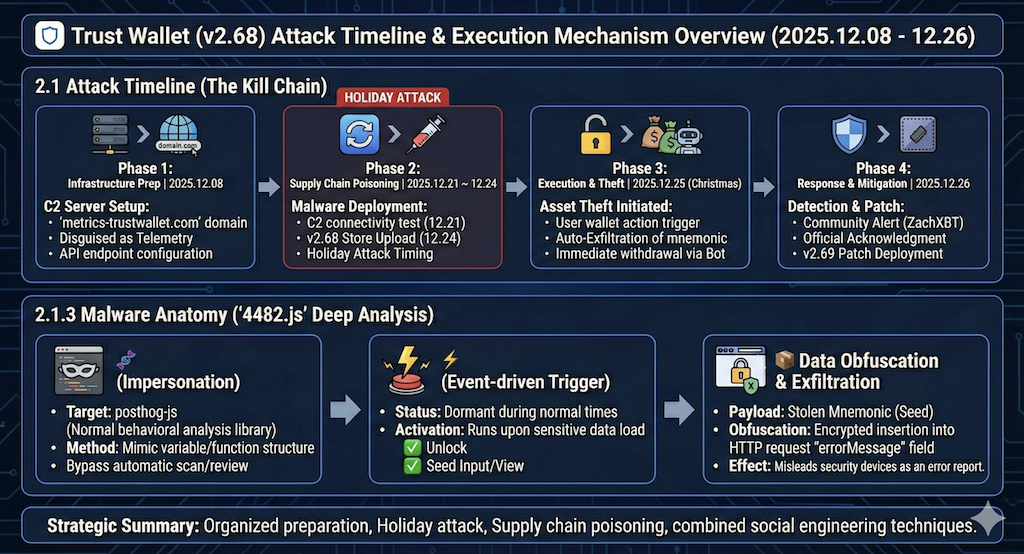

2.1 Attack timeline and execution stages

This incident appears to be a coordinated operation with at least three weeks of preparation, not a one off event. The attacker executed a staged plan: (1) infrastructure setup, (2) payload development and testing, (3) supply-chain distribution, and (4) theft and laundering.

2.1.1 Infrastructure preparation (2025-12-08)

About two weeks before the main theft window, the attacker registered the domain metrics-trustwallet.com. The naming is likely intentional, designed to

resemble a legitimate Trust Wallet monitoring or telemetry endpoint and create confusion.

The registrar is identified as “NICENIC INTERNATIONAL.” At this stage, the attacker appears to have prepared C2 infrastructure and an API endpoint

(api.metrics-trustwallet.com) to reliably collect and store stolen data.

2.1.2 Supply-chain contamination and distribution (2025-12-21 to 12-24)

Initial queries toward the C2 infrastructure were observed starting December 21, consistent with pre-deployment testing (data collection, exfiltration, and

stealth).

On December 24, right before the Christmas holiday period, Trust Wallet extension v2.68 containing the malicious code was uploaded to the Chrome Web

Store. This timing aligns with a “holiday attack” pattern, where attackers exploit reduced monitoring and slower response during holidays.

2.1.3 Malicious payload analysis: 4482.js

Our analysis indicates the core malicious behavior resides in the hidden 4482.js file. The attacker used multiple techniques aimed at both evasion and

delaying analysis:

(1) Impersonation of legitimate libraries

The payload masqueraded as posthog-js, a widely used open-source user analytics library. Naming, structure, and call patterns were made to look

“normal,” likely to evade quick code reviews and automated scanning.

(2) Event-driven activation

The malicious logic did not run constantly. It was designed to trigger only during sensitive events when secrets are exposed (for example, password entry

for unlocking, seed phrase handling, or specific calls such as GET_SEED_PHRASE). This reduces suspicious behavior during routine browsing and makes

detection harder.

(3) Data hiding in outbound traffic

Seed phrase data was not sent in plain text. Instead, it appears to have been hidden in non-standard HTTP fields such as errorMessage in encrypted or

encoded form, making the traffic look like ordinary error reporting and reducing the chance of being flagged by IDS/IPS or basic traffic review.

2.1.4 Theft and response (2025-12-25 to 12-26)

On December 25, users who had updated to v2.68 exposed their mnemonic seeds at the moment they used the wallet (unlocking, seed entry, etc.). The

attacker then used an automated sweeping bot to rapidly drain funds. Public warnings from on-chain investigators such as ZachXBT and 0xakinator

amplified awareness in the community, and Trust Wallet officially acknowledged the incident on December 26 and released the patched v2.69 version.

3. Detailed Victimology and Loss Assessment Summary

Loss valuation method

Losses were calculated using a strict price snapshot at the incident date (December 24, 2025), for example BTC $87,000, ETH $2,930, and MATIC $0.10.

This conservative approach reduces distortion from post-incident price swings.

3.1 Victim counting method

Victim counts are based on unique wallet addresses:

- One wallet address is counted as one victim, even if multiple transactions exist

- Dusting transfers are excluded

- Fake token activity is excluded

Important limitation: address count is not the same as “number of people.” Many users operate multiple wallets. With typical duplication assumptions, 1,311 wallet addresses may correspond to roughly 437 to 655 individuals (about one-third to one-half of the address count).

3.2 Final confirmed totals (verified)

- Unique victim wallets (addresses): 1,311

- Transaction count: 1,906

- Total losses (USD): 7,239,223.79

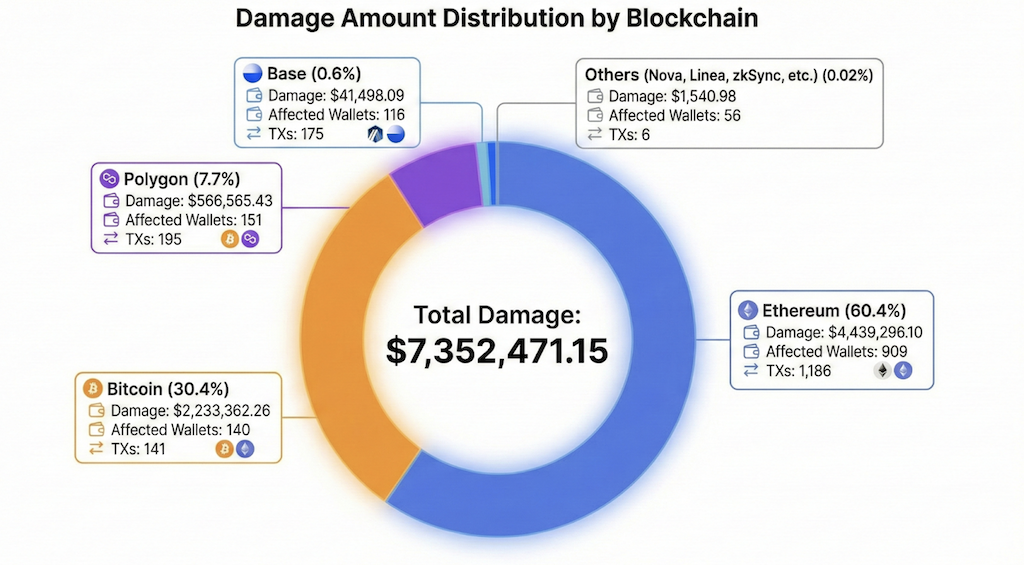

3.3 Losses by chain

Losses were confirmed across both EVM-compatible networks and Bitcoin, with Ethereum representing the largest share by value:

- Ethereum: 909 wallets, 1,186 tx, $4,439,296.10

- Bitcoin: 140 wallets, 141 tx, $2,233,362.26

- Polygon: 151 wallets, 195 tx, $566,565.43

- Arbitrum: 173 wallets, 203 tx, $70,208.29

- Base: 116 wallets, 175 tx, $41,498.09

- Others (Nova, Linea, zkSync, etc.): 56 wallets, 6 tx, $1,540.98

Note: “victim wallet count by chain” is measured per chain. If the same user is affected on multiple chains, they can be counted multiple times at the chain level. Also, bridge/swap labeling can introduce minor overlaps, so chain-level figures may not sum perfectly to the global total.

3.4 Top stolen assets and concentration

A total of 239 asset types were stolen, but losses are heavily concentrated in a few major assets:

- Top 3 assets (ETH, BTC, MATIC): 84.4% of total losses

- ETH: $3,312,855.48 (about 1,130 ETH)

- BTC: $2,233,362.26

- MATIC: $566,565.43 (about 5.66M MATIC at $0.10)

Stablecoin note:

USDT: $539,643.99 (about 7.5% of total)

3.5 Deep insights

(1) Bitcoin losses: fewer victims, larger amounts

Bitcoin represents only 140 victim wallets (about 10.7% of all victims) but accounts for $2,233,362.26 (about 30.9% of total losses). The average loss per

Bitcoin wallet is about $15,953.

Interpretation: some users likely used Trust Wallet to hold BTC for longer-term storage rather than frequent trading, resulting in larger balances and

heavier losses concentrated in fewer wallets.

(2) Concentration and “whale effect”

Losses follow a classic long-tail pattern: many small losses, plus a few very large wallets that meaningfully inflate the total.

For example, Top Victim #1 (0x062a31bd836cecb1b6bc82bb107c8940a0e6a01d) lost about $2,566,742.43, roughly 35.5% of the total $7,239,223.79.

If you exclude this one wallet, the average loss across the remaining 1,310 wallets drops to about $3,566.78 (down from the overall average of $5,521.91).

Practical takeaway: response is most effective when run on two tracks at once: (1) an accelerated freeze/recovery track focused on the highest-loss

wallets, and (2) a standardized reporting/support track for the broader victim population.

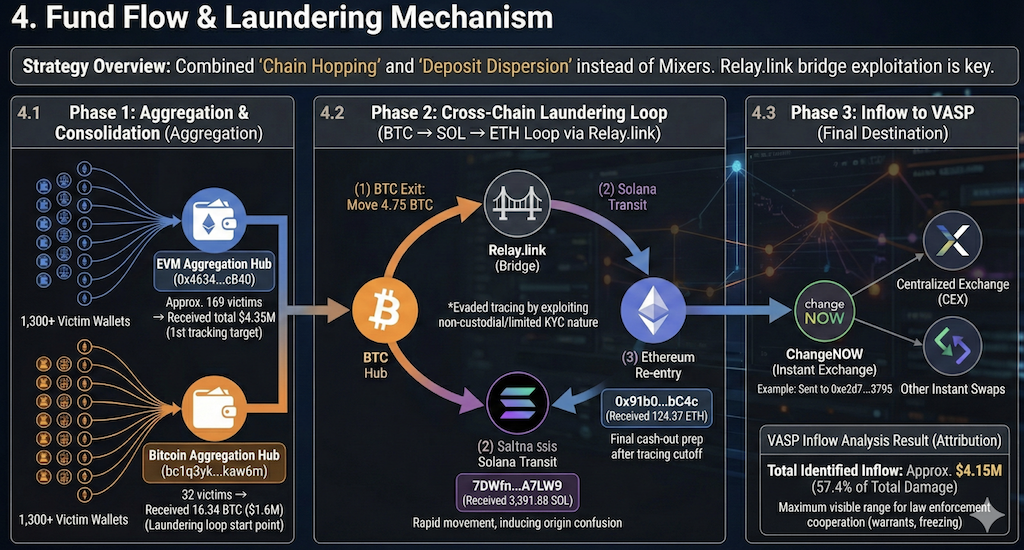

4. Fund Flow and Laundering Mechanics

Instead of relying mainly on traditional mixers, the attacker combined (1) repeated cross chain moves (chain hopping) and (2) broad distribution across many deposit addresses at centralized exchanges and instant swap services.

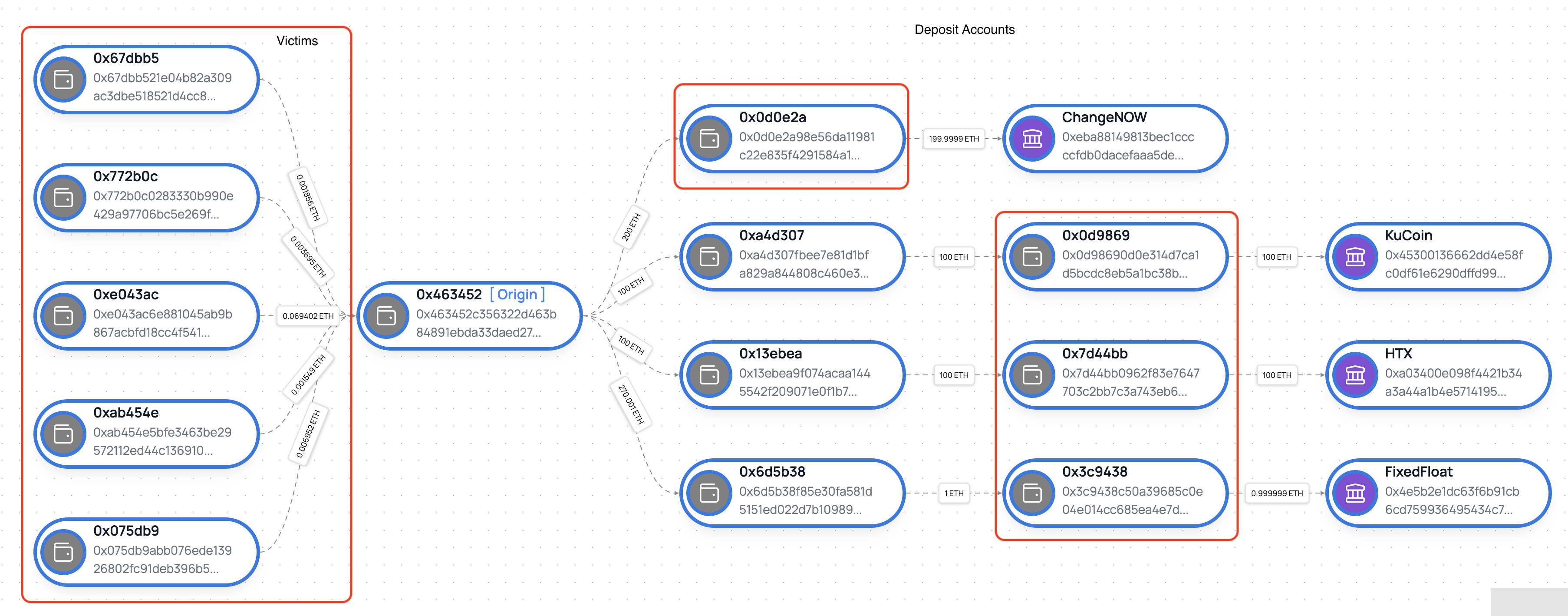

4.1 Step 1: Aggregation (funneling and consolidation)

Immediately after theft, the attacker consolidated funds from about 1,300 victim wallets into a small set of intermediate aggregator wallets. This improves operational efficiency (gas optimization and automation) and sets up the “concentrate then disperse” pattern that complicates investigation.

A) EVM aggregation hub

- Address: 0x463452C356322D463B84891eBDa33DAED274cB40

- Summary: received about $4.35M from roughly 169 victims

- Why it matters: more than 60% of EVM-side stolen value appears to have passed through this wallet, making it a primary investigative target.

B) Bitcoin aggregation hub

- Address: bc1q3ykewj0xu0wrwxd2dy4g47yp75gxxm565kaw6m

- Summary: received 16.34 BTC (about $1.6M) from 32 victims

- Why it matters: it functions as a launch point for the cross-chain laundering loop.

4.2 Step 2: Cross-chain laundering loop (BTC → SOL → ETH)

The most technically important finding is that the attacker built a deliberate three stage laundering loop through Solana and Ethereum to break Bitcoin trace continuity. This design can cause tracing to “appear to stop” if investigators only follow one chain or a single explorer. Relay.link served as the connective infrastructure.

(1) BTC exit

- From: Bitcoin aggregation wallet (bc1q3yk…)

- Action: about 4.75 BTC (about $465,500 at the time) sent to Relay.link

- Intent: weaken the UTXO-based trace line by moving funds into a bridging context

(2) Solana transit

- To: 7DWfnYqLzAjsKsPcNmZU24p8mbPSNyrQhGJBMn7A7LW9

- Received: about 3,391.88 SOL

- Behavior: short holding period, then prepared to move again to Ethereum via Relay.link

- Why Solana: fast finality and low fees make rapid splitting, swapping, and re-bridging easier.

(3) Ethereum re-entry and cash-out path

- To: 0x91b05D18A916e4834E48378B3A4f1391C489bC4c

- Received: about 124.37 ETH (about $364,404)

- Next: quickly forwarded to a ChangeNOW deposit address 0xe2d7adc202f7aeb2ede69b52a53ef340b5933795

Conclusion

This loop is engineered to defeat linear, single-chain tracing. Relay.link’s non-custodial model and limited KYC touchpoints appear to have been used to

loosen attribution links.

4.3 Inflows to service providers (VASP attribution)

At the final stage, funds moved into centralized exchanges (CEX) or instant swap services. The confirmed, identified inflow total is about $4.15M, roughly 57.4% of total losses. This represents the most actionable window for warrants, KYC/log requests, and freezing actions.

Top identified destinations

ChangeNOW: $2,345,903 (56.5% of identified inflows)

Notes: heavily used across both EVM (about $1.74M) and BTC (about $0.6M). Behavior suggests it was used as a practical “mixer substitute.”

FixedFloat: $852,341 (20.5%)

Notes: BTC-heavy inflows. A structuring pattern was observed (for example, depositing in chunks such as 10 ETH units).

KuCoin: $367,236 (8.8%)

Notes: mostly BTC. As a KYC-based exchange, the chance of obtaining identity information is relatively higher.

HTX (Huobi): $293,938 (7.1%)

Notes: EVM inflows confirmed, including stablecoin routes.

Others: additional small destinations exist; some funds remain untraced or appear to remain in attacker-controlled wallets.

EVM Inflow example

This diagram maps the movement of funds from multiple "Victim" wallets to a central "Origin" address (0x463452). From there, the assets are distributed through various intermediate wallets before landing in deposit accounts at exchanges like ChangeNOW, KuCoin, HTX, and FixedFloat.

Source: CATV

Investigative focus: ChangeNOW

ChangeNOW processing more than half of identified inflows is critical. Even “no-signup” swap services often apply internal risk controls for high-volume, high-risk flows, including transaction holds, enhanced verification, and potential freezes. In practice, ChangeNOW engagement is directly tied to recovery potential.

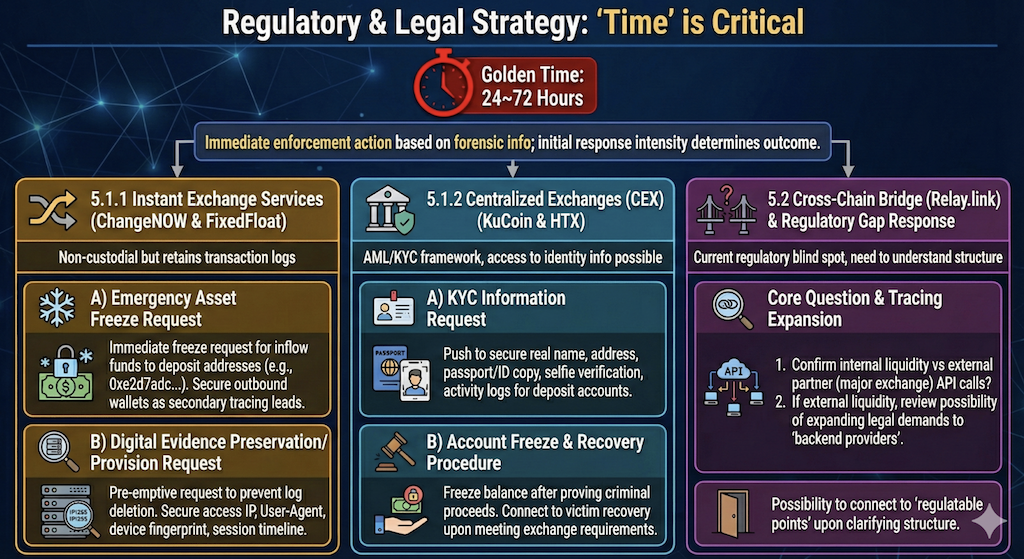

5. Regulatory and Legal Response Strategy

Forensic findings must translate into immediate actions. Speed is the deciding factor: funds are quickly swapped, split, and moved again after deposit. The first 24 to 72 hours typically determine outcomes.

5.1 Target-specific actions

5.1.1 ChangeNOW and FixedFloat (instant swap services)

Although these services may operate closer to non-custodial models, they still retain operational logs and metadata at the moment swaps occur.

Recommended actions:

A) Emergency freeze requests

Send urgent freeze requests tied to identified deposit addresses (for example, 0xe2d7adc… and other linked addresses). Even if funds already moved

out, the outbound wallet addresses become high-value leads for second-stage tracing.

B) Evidence preservation and production requests

Request preservation of logs to prevent routine deletion, then pursue formal legal processes for production. Key artifacts can include access IPs, user-

agent strings, device/browser fingerprints (where available), and session timelines, all of which can help infer attacker location and tooling.

5.1.2 KuCoin and HTX (centralized exchanges)

These exchanges typically maintain AML/KYC frameworks, making identity-level attribution more feasible.

A) KYC information requests

For accounts receiving deposits (for example, KuCoin deposit addresses such as 0x0d986… and others), pursue account holder identification, ID

documents, selfie verification, and activity logs.

B) Account freezes and restitution workflows

If criminal proceeds can be substantiated, exchange balances may be frozen and routed into restitution or law-enforcement custody workflows.

Operationally, each exchange has required formats (case number, authority letter, address and TX list, victim statements, etc.), which must be prepared

precisely.

5.2 Relay.link and the regulatory gap

Relay.link currently sits in a regulatory gray area. However, deeper structure analysis may reveal actionable touchpoints. Key questions include:

- Does Relay.link execute swaps using its own liquidity pools, or does it route via external partners (such as major exchanges or liquidity providers) through APIs?

- If external liquidity is involved, can legal requests be extended to the upstream liquidity provider that sits behind the bridge flow?

As the internal routing becomes clearer, links that initially look “broken” may reconnect to entities that are within regulatory reach.

6. Conclusion and Recommendations

This Trust Wallet extension compromise resulted in confirmed losses of about $7.24M, clearly demonstrating how supply chain weaknesses in widely distributed client software can translate into immediate, severe user losses. The attacker showed a high level of preparation and technical capability, executing a full lifecycle: infrastructure setup, distribution through an official update channel, and multi-chain laundering via chain hopping.

Even when attackers aim for “perfect concealment,” on-chain transparency makes it difficult to hide everything indefinitely.

The cross chain route (BTC → SOL → ETH → ChangeNOW) has already been identified, and the fact that more than 57% of total losses flowed into service providers (exchanges and swap services) keeps open a real window for freezes and recovery.

What matters now is fast execution:

For investigators: immediately initiate cross-border cooperation using the report’s deposit addresses and flow mappings, prioritizing freezes and

evidence preservation.

For victims: pursue relief through official procedures (working with investigators, civil/criminal actions, and formal freeze requests), while staying alert for

secondary scams.

For wallet providers: urgently strengthen code-signing verification, third-party library auditing, and real-time detection/alerting for suspicious transaction

patterns.

Final warning: recovery scams

Secondary scams are common after incidents like this. Anyone claiming they can “recover your funds” directly should be treated as suspicious. Only follow official processes through recognized law-enforcement channels and Trust Wallet’s official communications.

195 reads